SOLID Principles: Writing Clean Code

Image source: Geeks for Geeks

Author: Hayden Hargreaves

Published: 11/10/2025

Background

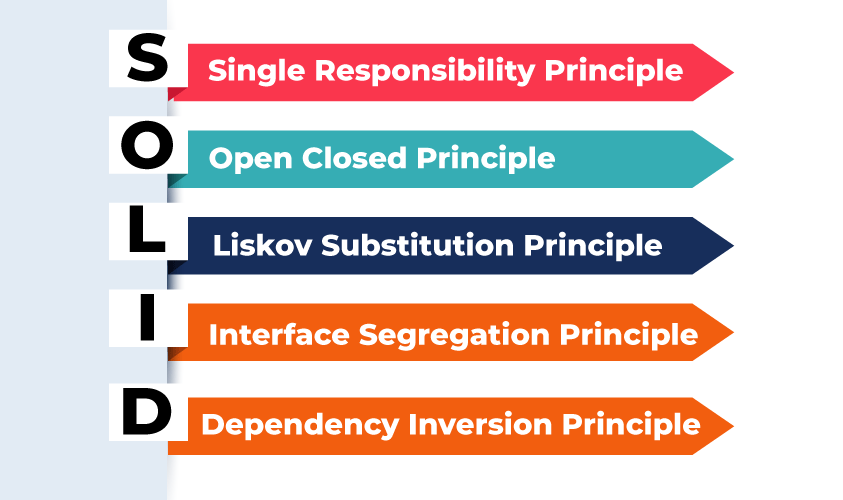

If you have not heard of the SOLID principles, you are in the right place! SOLID is an acronym for the first five object-oriented design (OOD) principles, invented by Robert C. Martin, commonly known as Uncle Bob. The goal of the SOLID principles is to establish best practices for developing maintainable and extensible software. Adapting these principles into your own code can help you avoid code smells, refactor code and develop Agile software.

"If you think good architecture is expensive, try bad architecture." ~Robert "Uncle Bob" Martin

The five principles are as follows:

- S - Single-responsibility Principle

- O - Open/closed Principle

- L - Liskov Substitution Principle

- I - Interface Segregation Principle

- D - Dependency Inversion Principle

This article serves as an introduction, not a comprehensive guide. However, a simple understanding of the principles can help you level up as a developer!

Key Takeaways

- Single Responsibility Principle: Each class should do one thing and have only one reason to change.

- Open/Closed Principle: Code should be open for extension but closed for modification.

- Liskov Substitution Principle: Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types without affecting program correctness.

- Interface Segregation Principle: Never force a client to depend on methods it does not use.

- Dependency Inversion Principle: Depend on abstractions, not on concrete implementations.

Object-Oriented Programming Refresher

A basic understanding of object-oriented programming (OOP) is expected for optimal success when reading this article. Regardless, a simple refresher can't hurt! Object-oriented programming is precisely what it sounds like, object-based programming. Code written in OOP languages is organized into "objects", which are self-contained units that combine data (attributes) and functions that operate on the data (methods). The OOP approach can simplify complex systems, promote code reusability and modularity, which makes OOP code easier to maintain and scale. There are four main principles of object-oriented programming: encapsulation, inheritance, abstraction and polymorphism. I will write a dedicated article about these four principles soon, which will also be found here in my journal.

To understand the SOLID principles, it is essential to remember what a class is: a class is a blueprint or template for creating objects. An object is a unique instance of a class.

There are many object-oriented languages, and the concepts taught in this article are not unique to a specific language; they can be applied to any language that implements OOP structure (even Python!). Some languages include: C++, C#, Java, Ruby, and others. The examples provided in this article will be in C++, but as mentioned previously, they apply to any OOP language!

Single-Responsibility Principle

The Single-Responsibility Principle states:

"A class should have one and only one reason to change, meaning that a class should have only one job." ~Robert "Uncle Bob" Martin

The Misunderstood Principle

The SRP is the simplest, yet most commonly misunderstood principle. The goal of the SRP is to prevent unexpected side effects by keeping each unit (class) simple and with only a single purpose. A class with many responsibilities will often need to be modified as requirements change, which can lead to more bugs. When a class is changed, it can impact classes that depend on it, which can result in unexpected bugs in code that did not seem to change. However, a class with a single responsibility will be changed much less, reducing the number of sneaky bugs that result from code refactors.

Easier to Understand

Another benefit of implementing the single-responsibility principle is that the resulting code becomes much easier to understand. A class with a single purpose is much easier to explain to a coworker or intern. However, this is another area of shared misunderstanding. Some developers take the SRP a bit too far and oversimplify their code, for example, by writing a new class for each function. When they later want to write some real code, they need to inject dozens of dependencies to achieve a single task!

A healthy balance of responsibility and simplicity exists, which can be challenging to understand at first. The best thing you can do is keep the SRP in mind, but do not follow it too strictly. Do not use it as your "programming bible." Use common sense; there is no point in classes that only contain a single function!

Code Example

To display this concept, we will examine a Shape class that needs to be drawn to an output. Below is

an implementation that does not adhere to the single-responsibility principle.

class Shape {

public:

Shape(double w, double h) : width(w), height(h) {};

// Responsibility 1: Core Business Logic (Math)

double calculateArea() const {

return this->width * this->height;

}

// Responsibility 2: Presentation/Output (Drawing)

void draw() const {

// Imagine complex rendering code here...

std::cout << "Drawing a rectangle of size " << this->width << "x"

<< this->height << "\n";

}

private:

double width;

double height;

};

However, as the comments note, this class has more than one responsibility. The class is responsible for storing shape data, computing the area, and rendering it to the output. Imagine we have hundreds of shapes, we don't want to write hundreds of different ways to render each shape! This example is a tad simple, but it helps us understand why we need to split responsibilities as code scales.

To fix this, we can create a ShapeRenderer class and simplify our Shape class.

// 1. ShapeSRP: Responsibility = Core Business Logic ONLY (Data and Math)

class ShapeSRP {

public:

ShapeSRP(double w, double h) : width(w), height(h) {}

// Methods for data access and core calculation

double getWidth() const { return width; }

double getHeight() const { return height; }

// Stays here as it's the core purpose of the data

double calculateArea() const {

return width * height;

}

private:

double width;

double height;

};

// 2. ShapeRenderer: Responsibility = Presentation/Output ONLY

class ShapeRenderer {

public:

// This class's sole job is to handle how the Shape is visualized.

void draw(const ShapeSRP& shape) const {

// The rendering logic is isolated here.

std::cout << "--- Graphics Renderer Output ---\n";

std::cout << "Drawing a shape with area: " << shape.calculateArea() << "\n";

std::cout << "Using dimensions: " << shape.getWidth() << "x" << shape.getHeight() << "\n";

}

};

We have successfully implemented a scalable and modular class that can be used with various shapes. Using polymorphism, we can achieve an even better solution, which is not the focus of this article, but further encourages the idea.

#include <cmath>

#include <iostream>

// 1. Abstract Base Class: Defines the contract for all shapes

class Shape {

public:

// Core Business Logic: Must be implemented by derived classes

virtual double calculateArea() const = 0;

// Virtual destructor is crucial for proper cleanup with polymorphism

virtual ~Shape() = default;

};

// Concrete Shape 1: Rectangle

class Rectangle : public Shape {

public:

Rectangle(double w, double h) : width(w), height(h) {}

// Implements the specific area calculation for a rectangle

double calculateArea() const override { return width * height; }

// Getters needed for the renderer

double getWidth() const { return width; }

double getHeight() const { return height; }

private:

double width;

double height;

};

// Concrete Shape 2: Circle

class Circle : public Shape {

public:

Circle(double r) : radius(r) {}

// Implements the specific area calculation for a circle

double calculateArea() const override { return M_PI * radius * radius; }

// Getters needed for the renderer

double getRadius() const { return radius; }

private:

double radius;

};

// Renderer Interface (Contract for drawing)

class Renderer {

public:

// The renderer must be able to handle any kind of Shape

virtual void render(const Shape &shape) const = 0;

virtual ~Renderer() = default;

};

// Console Renderer Implementation

class ConsoleRenderer : public Renderer {

public:

void render(const Shape &shape) const override {

std::cout << "\n--- Console Output (Simple) ---\n";

// This dynamic_cast is often necessary when a Renderer needs specific data,

// but it's important to keep the logic here, separate from the Shape class!

if (const auto *rect = dynamic_cast<const Rectangle *>(&shape)) {

std::cout << "Type: Rectangle\n";

std::cout << "Dimensions: " << rect->getWidth() << "x"

<< rect->getHeight() << "\n";

} else if (const auto *circ = dynamic_cast<const Circle *>(&shape)) {

std::cout << "Type: Circle\n";

std::cout << "Radius: " << circ->getRadius() << "\n";

} else {

std::cout << "Type: Unknown Shape\n";

}

// **Polymorphic call:** This works for all shapes!

std::cout << "Calculated Area: " << shape.calculateArea() << "\n";

}

};

This has taken our shape renderer example to new heights! But by now, you should be able to understand the pros and cons of the Single-responsibility principle.

Open/Closed Principle

The Open/Closed Principle states:

"Objects or entities should be open for extension but closed for modification." ~Bertrand Meyer

This means a class should be extensible without requiring modifications to the class itself.

The general idea of the Open/Closed Principle (OCP) is excellent! It requires a developer to write code that can be upgraded or extended without requiring modifications to existing code. This effect prevents extensions from requiring the developer to adapt all classes that depend on the target class. But Bertrand Meyer suggests that inheritance is used to achieve this:

“A class is closed, since it may be compiled, stored in a library, baselined, and used by client classes. But it is also open, since any new class may use it as parent, adding new features. When a descendant class is defined, there is no need to change the original or to disturb its clients.” ~Bertrand Meyer

This is a problem because it frequently introduces tight coupling if subclasses depend on the implementation of a parent class. For that reason, "Uncle Bob" revised the principle to the Polymorphic Open/Closed Principle. Using interfaces instead of superclasses (a class that has subclasses) allows different implementations, which can be swapped and changed with relative ease. Furthermore, the calling (using) code does not need to be changed, as long as the interface's requirements are met.

Another significant benefit of using this polymorphic guideline is that it introduces an additional level of abstraction, which enables loose coupling. Interface implementations are distinct and have no relation to one another, and share no code. But if the interfaces should share some code, then composition and inheritance can be used.

Code Example

To reinforce this point, a simple employer bonus calculation program will be written in two different ways: one that violates the OCP, and one that does not. It will be up to you to judge the effectiveness of each solution, and therefore the effectiveness of the rule!

In the example below, we violate the Open/Closed principle because any time a new employee type is

added, the BonusCalculator class must be updated to match.

enum EmployeeType { MANAGER, DEVELOPER, SALES };

class Employee {

public:

Employee(EmployeeType type, double salary) : type(type), salary(salary) {}

EmployeeType getType() const { return type; }

double getSalary() const { return salary; }

private:

EmployeeType type;

double salary;

};

// VIOLATION: This class must be MODIFIED every time a new EmployeeType is added.

class BonusCalculator {

public:

double calculateBonus(const Employee &emp) const {

double salary = emp.getSalary();

if (emp.getType() == MANAGER) {

// Manager gets 10% bonus

return salary * 0.10;

} else if (emp.getType() == DEVELOPER) {

// Developer gets 5% bonus

return salary * 0.05;

} else if (emp.getType() == SALES) {

// Sales gets a fixed bonus

return 500.0;

}

// If we add 'HR', we MUST modify and recompile this function.

return 0.0;

}

};

To fix this example, we can take three steps:

First, we can use abstraction via an Abstract Base Class (a class that cannot be instantiated, ABC)

and polymorphism. This allows us to extend the base Employee class and let the final BonusProcessor

class grow via polymorphism.

The EmployeeBase class is open for extension since many more types can implement it without

modifying the class itself.

// 1. Base Class: Defines the contract

class EmployeeBase {

public:

EmployeeBase(double salary) : salary(salary) {}

// Virtual function (the key to polymorphism)

virtual double calculateBonus() const = 0;

virtual ~EmployeeBase() = default;

protected:

double getSalary() const { return salary; }

private:

double salary;

};

Now, we can create some different types of employees that inherit (implement) the EmployeeBase ABC.

// 2. Concrete Implementations

class Manager : public EmployeeBase {

public:

Manager(double salary) : EmployeeBase(salary) {}

// Implements its unique bonus logic

double calculateBonus() const override { return getSalary() * 0.10; }

};

class Developer : public EmployeeBase {

public:

Developer(double salary) : EmployeeBase(salary) {}

// Implements its unique bonus logic

double calculateBonus() const override { return getSalary() * 0.05; }

};

// Adding a brand new type (e.g., HR) requires NO modification to existing code!

class HRSpecialist : public EmployeeBase {

public:

HRSpecialist(double salary) : EmployeeBase(salary) {}

double calculateBonus() const override { return getSalary() * 0.03; }

};

Finally, we can create the BonusProcessor class, which interacts only with the EmployeeBase ABC,

making it closed for modification.

// 3. ADHERENCE: This class is CLOSED for modification.

class BonusProcessor {

public:

// This function doesn't need to know the specific type (Manager, Developer,

// etc.) It relies only on the contract (virtual function) defined in

// EmployeeBase.

double processBonus(const EmployeeBase &emp) const {

return emp.calculateBonus();

}

};

Hopefully, you can see how powerful this principle can be when implemented correctly. Code that adheres to the open/closed principle is easy to scale, expand and upgrade.

Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov Substitution Principle states:

"Let q(x) be a property provable about objects of x of type T. Then q(y) should be provable for objects y of type S where S is a subtype of T." ~Barbara Liskov

This means that every subclass (derived class) should be substitutable for their base (parent) class.

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) is a subtyping definition known as strong behavioral subtyping. Meaning, a class that a derived class has replaced should continue to function as expected, therefore defining a semantic relation, not just a syntactic relation.

Code Example

This principle can be challenging to understand; for simplicity's sake, we will examine only a violation of the principle—the well-known Rectangle/Square Problem.

class Rectangle {

public:

Rectangle(int w, int h) : width(w), height(h) {}

virtual void setWidth(int w) { this->width = w; }

virtual void setHeight(int h) { this->height = h; }

int getArea() const { return this->width * this->height; }

protected:

int width;

int height;

};

// Subclass that violates LSP

class Square : public Rectangle {

public:

Square(int size) : Rectangle(size, size) {}

// LSP VIOLATION: Square alters the expected behavior of setters.

// Setting width MUST also set height, breaking the client's expectation

// that width and height can be set independently.

void setWidth(int w) override {

this->width = w;

this->height = w; // Mutates height

}

void setHeight(int h) override {

this->height = h;

this->width = h; // Mutates width

}

};

In the context of mathematics, a square is a rectangle. However, in the context of programming, forcing a square to inherit from a rectangle typically violates the LSP. This violation occurs because the settings are being overridden, and each value is set individually from each method. The expectation for a rectangle is that the height and width will be set independently!

Interface Segregation Principle

The Interface Segregation Principle states:

"A client should never be forced to implement an interface that it doesn’t use, or clients shouldn’t be forced to depend on methods they do not use." ~Robert "Uncle Bob" Martin

The goal of the interface segregation principle (ISP) is that large, general-purpose interfaces should be broken down into smaller, more specific interfaces. Doing so means that client classes only need to be aware of the methods that are directly relevant to them.

Code Example

Imagine a scenario where we have various types of printers, such as simple, multifunctional, and

others. We create a single, large interface, IMachine, that attempts to encompass all the functionality.

This multi-use interface is what's known as a fat interface.

// VIOLATION: A single, "fat" interface with methods not all clients need.

class IMachine {

public:

virtual void print(const std::string& document) const = 0;

virtual void scan(const std::string& document) const = 0;

virtual void fax(const std::string& document) const = 0;

virtual ~IMachine() = default;

};

// A SimplePrinter only needs to print, but it is forced to implement scan and fax.

class SimplePrinter : public IMachine {

public:

void print(const std::string& document) const override {

std::cout << "SimplePrinter: Printing " << document << ".\n";

}

// PROBLEM: SimplePrinter is forced to implement methods it doesn't use.

void scan(const std::string& document) const override {

// This implementation is a lie/waste, or throws an exception.

std::cerr << "SimplePrinter: ERROR! Cannot scan.\n";

}

void fax(const std::string& document) const override {

// This forces unnecessary dependencies and potential runtime errors.

std::cerr << "SimplePrinter: ERROR! Cannot fax.\n";

}

};

The SimplePrinter is forced to implement the scan and fax methods, which are functions the printer

does not have, therefore violating the LSP! However, a simple fix exists: splitting the interface

into separate interfaces.

// 1. Segregated Interface: Printing capability

class IPrinter {

public:

virtual void print(const std::string &document) const = 0;

virtual ~IPrinter() = default;

};

// 2. Segregated Interface: Scanning capability

class IScanner {

public:

virtual void scan(const std::string &document) const = 0;

virtual ~IScanner() = default;

};

// 3. Segregated Interface: Fax capability

class IFaxDevice {

public:

virtual void fax(const std::string &document) const = 0;

virtual ~IFaxDevice() = default;

};

Once the interfaces have been thinned, we can implement them again, but this time, in a way that does not violate the ISP.

// ADHERENCE: SimplePrinter now only implements the interface it needs.

class SimplePrinterSRP : public IPrinter {

public:

void print(const std::string &document) const override {

std::cout << "SimplePrinter: Printing " << document << ".\n";

}

// No more forced scan or fax methods! The client is clean.

};

// The MultiFunctionPrinter implements ALL the needed interfaces (composition)

class MultiFunctionPrinter : public IPrinter,

public IScanner,

public IFaxDevice {

public:

void print(const std::string &document) const override {

std::cout << "MFP: Printing " << document << ".\n";

}

void scan(const std::string &document) const override {

std::cout << "MFP: Scanning " << document << ".\n";

}

void fax(const std::string &document) const override {

std::cout << "MFP: Faxing " << document << ".\n";

}

};

Dependency Inversion Principle

The Dependency Inversion Principle states:

"Entities must depend on abstractions, not on concretions. It states that the high-level module must not depend on the low-level module, but they should depend on abstractions." ~Robert "Uncle Bob" Martin

This means that a class should rely on abstractions (interfaces or abstract base classes) rather than concrete implementations. The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) is a specific methodology for creating loosely coupled modules. When implemented, the DIP allows high-level modules to exist independently of the low-level modules.

A nice analogy I found states:

"In a software development team, developers depend on an abstract version control system (e.g., Git) to manage and track changes to the codebase. They don't depend on specific details of how Git works internally." ~geeksforgeeks

Code Example

To illustrate the DIP, we will use an example in which a high-level Notifier needs to send messages

to a low-level SMSService.

The initial implementation will work fine; however, it violates the DIP. What will happen if the

requirements change and the Notifier needs to send messages to a new service, such as an EmailService?

// Low-level Module (The Detail)

class SMSService {

public:

void sendSMS(const std::string &recipient, const std::string &message) const {

std::cout << "SMSService: Sending SMS to " << recipient << ": '" << message

<< "'\n";

}

// No abstraction/interface here

};

// High-level Module (The Logic)

class Notifier {

public:

Notifier(const std::string &recipient) : recipient(recipient) {}

// DIP VIOLATION: Notifier (high-level) directly depends on SMSService

// (low-level).

void send(const std::string &message) const {

SMSService smsService; // Direct, hard dependency on the concrete class

smsService.sendSMS(recipient, message);

}

private:

std::string recipient;

};

By updating the code to adhere to the DIP, we can allow our Notifier class to send messages to any

client through the use of an abstraction.

// 1. Abstraction (The Contract/Interface)

class IMessageSender {

public:

virtual void sendMessage(const std::string &recipient,

const std::string &message) const = 0;

virtual ~IMessageSender() = default;

};

Then, we can create our clients; for this example, we only need two of them to demonstrate the power of the Dependency Inversion Principle.

// 2. Low-level Module depends on Abstraction (The Detail)

class SMSServiceDIP : public IMessageSender {

public:

void sendMessage(const std::string &recipient,

const std::string &message) const override {

std::cout << "SMSServiceDIP: Sending SMS to " << recipient << ": '"

<< message << "'\n";

}

};

// We can easily add a new service without touching the Notifier!

class EmailServiceDIP : public IMessageSender {

public:

void sendMessage(const std::string &recipient,

const std::string &message) const override {

std::cout << "EmailServiceDIP: Sending Email to " << recipient << ": '"

<< message << "'\n";

}

};

Finally, we can reimplement the Notifier class to depend only on the abstracted class and adhere

to the DIP.

// 3. High-level Module depends on Abstraction (The Logic)

class Notifier {

public:

// **Dependency Injection:** The concrete service is passed in via the

// constructor. The Notifier only knows about the IMessageSender interface!

Notifier(IMessageSender *service, const std::string &recipient)

: sender_(service), recipient_(recipient) {}

void send(const std::string &message) const {

// The high-level module uses the abstraction (interface).

sender_->sendMessage(recipient_, message);

}

private:

// Stores a pointer to the generic interface

IMessageSender *sender_;

std::string recipient_;

};

Don't Repeat Yourself

Before wrapping up, there is one more guideline that is not a part of the SOLID acronym but is relevant to programming in any paradigm. The Don't Repeat Yourself (DRY) rule states:

"Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system". ~Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas

The DRY rule is not directly part of the SOLID principles; however, it is commonly paired together as a result of Uncle Bob's strong feelings about the guideline.

"Duplication is the root of all evil in software". ~Robert "Uncle Bob" Martin

The purpose of the guideline is to encourage developers to avoid writing duplicate code in a system. Adhering to the DRY principle allows developers to create modular and reusable modules. Many believers in the system also believe that DRY code is more readable and easier to maintain and troubleshoot.

DRY is not the topic of this article, but if you would like to learn more, this article contains some solid points that support the guideline.

SOLID Only For OOP?

The focus of the SOLID principles is on object-oriented programming, but that does not mean they apply only to OOP. The terms "class" and "interface" can be abstracted down to their underlying philosophies, and the benefits of SOLID can be implemented anywhere these abstractions exist! For example, the single responsibility principle can be applied to teams, functions, modules and micro-services. The idea of the open/closed principle is desirable in any architecture.

The Liskov Substitution principle is a little bit harder to apply elsewhere, but anywhere a polymorphic relationship is observed, the principle can apply. The interface segregation principle encourages the breakdown of large, complex contracts, which is applicable in any design context and functional programming.

Finally, the dependency inversion principle encourages decoupling via abstraction, which serves as the core of many architectural design patterns. Therefore, the SOLID principles originated in an OOP context, but they offer "timeless wisdom" (Digital Ocean) for the development and maintenance of robust, scalable systems.

Conclusion

Understanding and applying the SOLID principles is not about memorizing five rules or following them strictly; it’s about learning to think more critically about design. Each principle—Single Responsibility, Open/Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion—offers a lens through which you can identify poor architecture and refactor toward cleaner, more maintainable code. When used thoughtfully, they lead to systems that are easier to test, extend, and collaborate on.

While SOLID principles were born in the world of object-oriented programming, their underlying philosophies reach far beyond it. Whether you’re structuring a microservice, designing a REST API, or writing a simple Python script, their concepts encourage scalability, flexibility, and craftsmanship. The ultimate goal isn’t to follow SOLID for the sake of it, but to build software that is a pleasure to read, modify, and maintain.